The Nature-Nurture Controversy: A Dialectical Essay

Accepted September 29, 2012

Keywords

behavior genetics, endophenotype, environmentalist, epigenetics, eugenics, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), hereditarian, heritability, monozygotic and dizygotic twins, systems approach

ABSTRACT

For millennia, scholars, philosophers and poets have speculated on the origins of individual differences in behavior, and especially the extent to which these differences owe to inborn natural factors (nature)versus life circumstances (nurture). The modern form of the nature-nurture debate took shape in the late 19th century when, based on his empirical studies, Sir Francis Galton concluded that nature prevails enormously over nurture. However, Galton's interest in eugenics undermined early research into the genetic origins of behavior, which did not re-emerge until the latter half of the 20th century when behavioral geneticists started to publish their findings from twin and adoption studies. Current consensus is that the nature versus nurture debate represents a false dichotomy, and that to progress beyond this fallacy will require the investigation of how both genetic and environmental factors combine to affect the biological systems that underlie behavioral phenotypes.

As a word by itself, nature is simply a proxy for the terms genetics or heredity. Nurture by itself is simply a proxy for the terms environment or experience, broadly construed. Separating the proxies by versus (vs) or adding the word controversy, as in the title of this paper, opens a Pandora's box going back to post-Darwinian times. An alias for the nature-nurture controversy is the heredity-environment debate, giving rise to the prototypes known as hereditarians and environmentalists, whose descendants still exist, although fortunately as outliers.

Roots of the Controversy

One of the great questions in western intellectual history concerns the origins of individual differences in behavior. Why do some suffer the scourges of mental illness while others appear immune to the most extreme levels of psychological stress? Why do some excel academically with little apparent effort while others struggle with even the simplest of school assignments? Why are some outgoing and cheerful while others withdrawn and forlorn? While he may not have been the first, William Shakespeare was certainly adept at using alliteration to capture the essence of the question. In The Tempest, the brutish Caliban is described as A devil, a born devil, on whose nature nurture can never stick.

The scientific juxtaposition of nature and nurture as competing accounts of the diversity of human behavior owes largely to Francis Galton, an English gentleman-scholar with an impeccable pedigree that includes Charles Darwin as his first cousin. He first juxtaposed the words in his 1874 book English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture, which was a follow-on to his famous book of 1869, Hereditary Genius. Both books focused on the theme of what makes men eminent.

"The phrase nature and nurture is a convenient jingle of words, for it separates under two distinct heads the innumerable elements of which personality is composed. Nature is all that a man brings with himself into the world; nurture is every influence from without that affects him after birth... In the competition between nature and nurture, when the differences in either case do not exceed those which distinguish individuals of the same race living in the same country under no very exceptional conditions, nature certainly proves the stronger of the two."

Galton's confidence in such a formulation was bolstered by his observations on the mental and physical characteristics of twins. Although he was one of the first to recognize the scientific value of studying twins, he was unable to reliably differentiate those who were monozygotic (MZ, genetically identical) from those who were dizygotic (DZ, genetically non-identical). Consequently, his research was based largely on anecdotal description of the behavior of twins, which nonetheless reinforced his earlier conclusions.

"The impression that all this evidence leaves on the mind is one of some wonder whether nurture can do anything at all, beyond giving instruction and professional training... There is no escape from the conclusion that nature prevails enormously over nurture when the differences of nurture do not exceed what is commonly to be found among persons of the same rank of society and in the same country."

Polarization in the Political and Policy Arenas

While Galton acknowledged the existence of environmental contributions, even if he accorded them a subservient role, his disciples were not as ecumenically inclined. Henry Herbert Goddard, one of the leading developmental psychologists of the early 20th century, was perhaps best known for having brought the IQ test, developed in Western Europe, to America. Goddard's strong hereditarian leanings were remarkable given that he devoted most of his professional career to the training of children with cognitive disabilities.

"...the consequent grade of intelligence or mental level for each individual is determined by the kind of chromosomes that come together with the union of the germ cells: That is but little affected by any later influences except such serious accidents as may destroy part of the mechanism."

This doctrine of genetic determinism when combined with another of Galton's intellectual progeny, would prove a volatile mix. Galton defined the term eugenics as

"...the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage."

Although it drew mainly from the progressive movement, eugenics gained broad support from across the political spectrum as it promised to address the social ills consequent to early 20th century industrialization. The eugenics movement, and for many the doctrine of genetic determinism upon which it was based, was ultimately discredited when the Nazis seized upon eugenic scholarship in an attempt to provide a scientific justification for their racial hygiene policies.

The decline in interest in genetic determinism was matched by increased interest in an antithetical but equally extreme view of human nature. In the 1920s, John B. Watson and his radical behaviorist colleagues had thrown down the gauntlet for environmentalism with his biological-free battle cry to the effect that given a dozen healthy infants he would guarantee that any one taken at random could be trained to be anything from a physician to a thief. With claims and counterclaims about the power of socialization and education to eradicate individual variation in intelligence test scores and mental disorders, the scientific controversy has endured even as its leaders have declared it intellectually bankrupt.

Twin studies came into their own after being put on a sound scientific basis in 1924 by Hermann Siemens in Germany, Kristine Bonnevie in Norway and Curtis Merriman in the USA. A rich harvest of adoption studies also contributed to their results. Regrettably, the studies were often conducted in an adversarial atmosphere by researchers disinterested in compromise. Seldom was it appreciated that the phenotype was an echo of a series of distal causes including the genotype, and that the same phenotype, mental retardation, for example, could arise from disparate influences ranging from poor prenatal nutrition or disease to hundreds of rare dominant and recessive gene loci. Indeed, a balanced review of the behavioral genetic literature of the time would have recognized that it provided no support for either extreme in the debate. The twin studies that had consistently found greater MZ than DZ resemblance, suggesting genetic factors, also inevitably reported less than perfect resemblance among MZ twins, implicating environmental factors. Adoption studies similarly reported resemblance among non-genetically related relatives even if this resemblance was less than that seen among genetically, and reared-together, relatives.

Dialectic Reconciliation

The science of genetics has much to teach social scientists not held captive by the ideology of the political right or the political left. As contemporary research on epigenetics has forcefully demonstrated, observed variation for complex traits in human populations will always arise from different combinations of genetic factors, environmental factors, and their interaction. Given the history of the nature-nurture controversy, it is easy to embrace the advice proffered by Theodosius Dobzhansky:

"The complexity of nature should not be evaded. The only way to simplify nature is to study it as it is, not as we would have liked it to be."

A systems approach to the study of genetically influenced traits and diseases is now widely accepted within the field of genetics, but the specifics have yet to be detailed and may be different across traits and species.

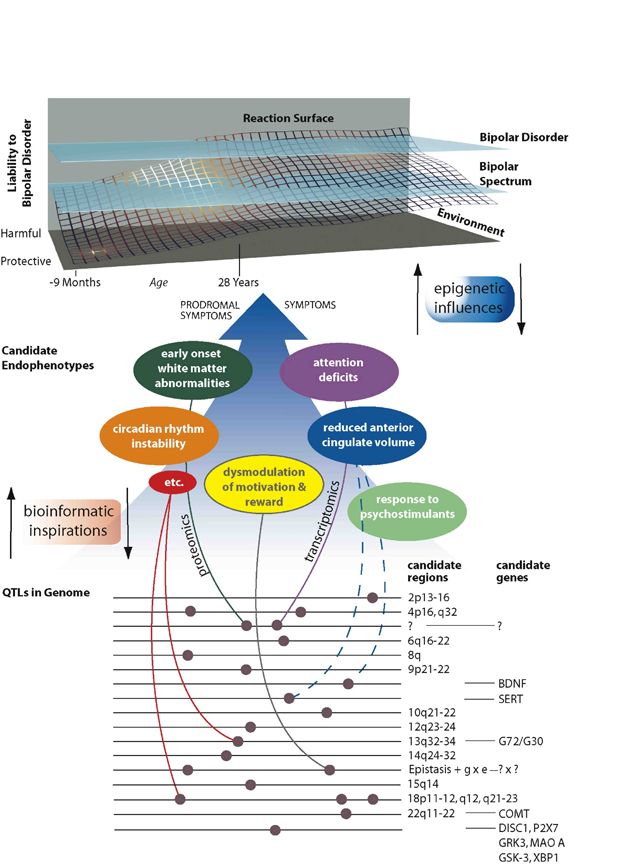

A start can be made, however. Figure 1 is a schema of the various known or suspected causes of bipolar disorder. It provides indicators of contributors all along the complex pathways from genotype to phenotype, highlighting, at the most distal end, the genes themselves. Many more such genes and gene regions will be uncovered with the rapid advances being made in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and the sequencing of entire genomes. Obviously, each trait-relevant gene can harbor multiple mutations that can enhance or diminish the likelihood of bipolar disordespecified at the far end of the system.

Six different, trait-relevant endophenotypes are conjectured that mediate the indirect influences of the named gene's products and regulatory functions on the bipolar spectrum. Such a separation of levels of influence in the gene-to-behavior pathway should facilitate research using a bottom-up approach, as it restrains complexity to the shorter path from genes to endophenotypes. The realms of developmental genetics are sketched in the upper part of the figure. Once the possible combinations of endophenotypes are launched at zygote formation, pre-, peri-, and postnatal influences are free to play their roles on expression of the bipolar liability along the time

(age) dimension. At the same time, environmental forces that can be construed as falling along a dimension of stifling to facilitating come into play. The net result of all these influences changes over time, resulting in variation in the trait level, which is indicated by a point on the reaction surface. No simplistic model that contains the vague terms nature and nurture can have the heuristic power to design and implement research in genetics that is possible with the systems approach presented here.

Cancer: A Prototype for a Complex Systems Approach

Recent developments in our understanding of the complex origins of cancer help to illustrate the superficiality inherent to placing nature and nurture in opposition. In 2000, Paul Lichtenstein and colleagues published the largest twin study of cancer ever reported, over 45,000 pairs. Twin concordance for specific cancers was generally low, less than 20%. Yet, MZ twins were more likely to be concordant than DZ twins, and more so for prostate than breast cancer, suggesting greater genetic involvement in the former as compared to the latter. Nonetheless, two of the most important discoveries of genetic variants associated with cancer risk are for breast cancer, BRCA1 and BRCA2, which are very rare, highly penetrant, genetic variants, and, therefore, their contribution to twin concordance is minimal. Alternatively, GWAS, which is targeted at common variants of modest phenotypic effect, has been somewhat more successful in identifying genetic variants associated with prostate than with breast cancer. In either case, the aggregate contribution of known genetic variants to cancer risk is remarkably small. The so-called missing heritability in cancer is likely to be found in common variants of even more modest effect, rare variants of moderate effect, and variation in gene-copy number. It is now clear that accounting for cancer's heritability on its own will not lead to improvements in cancer detection and treatment. Rather, what is required is a better understanding of how the expression of inherited sequence variants is affected by epigenetic and exogenous processes, i.e., how the environment modulates genetic effects.

Figure 1. An heuristic model of an endophenotype strategy for bipolar disorder research. The figure traces the continuum between suspected risk genes and genomic regions through endophenotypes to the distal disease phenotype. Pathways are subject to environmental modulation, and the model incorporates developmental and dynamic features of the disease through inclusion of the reaction surface. The figure is meant to represent a conceptual guide, rather than a definitive portrait of bipolar loci, endophenotypes, and systems processes. I.I. Gottesman and T.D. Gould, 2008; reproduced with permission.

The nature-nurture controversy arose out of our desire for a simple explanation for the origins of differences among us, and has helped to reinforce ideologically inspired conceptions of human nature. Science has, however, exposed the invalidity of this stark dichotomy by showing that both genetic and environmental factors are essentially involved in the development of all human traits.

Acknowledgments

This article will also appear in 2013 with minor changes in title in Brenner's Online Encyclopedia of Genetics, Second Edition: Vol 1-4. Stanley Maloy and Kelly Hughes (Eds) Academic Press., Waltham, MA. © Elsevier Science and Technology and reprinted by permission.

Further Readings

Baker C (2004) Behavioral genetics. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Washington, DC

Carey G (2003) Human genetics for the social sciences. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Goldman D (2012) Our genes, our choices. Academic Press, Waltham, MA

Gottesman II, Gould TD (2003) The endophenotype concept in psychiatry: etymology and strategic intentions. American J Psychiatry 160:636-645

Kim YK (2009) Handbook of behavior genetics. Springer, New York, NY

McGue M (2010) The end of behavioral genetics? Behavior Genetics 40:284-296

NCBI-Entrez Gene.

Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2002) Genetics and human behavior: the ethical context. Nuffield Council on Bioethics, London, UK

Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, McGuffin P (2008) Behavioral genetics, 5th Ed. WH Freeman, New York, NY

Plomin R, DeFries JC, Craig IW, McGuffin P (2003) Behavioral genetics in a postgenomic era. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC

Turkheimer E (2000) Three laws of behavior genetics and what they mean. Current Directions in Psychological Science 9:160-164

Concordance - For a discrete or categorical phenotype, such as whether or not someone has a disease, twin similarity is typically measured in terms of concordance. Concordance is the rate at which the co-twins of affected twins also have the disorder.

Endophenotype - term coined by Irving Gottesman and James Shields to refer to a measurable phenotype that is intermediate between the disease phenotype and its underlying genetic diathesis. The expectation is that the use of endophenotypes will improve researchers chances of identifying the genetic basis of disease, as endophenotypes sit closer to the primary gene product than do disease phenotypes.

Epigenetics - processes whereby gene expression is stably (over cell divisions or across generations) by factors other than the DNA sequence. Epigenetics is hypothesized to be an important mechanism to explain how genetically-identical monozygotic twins come to be discordant for inherited disease phenotypes.

Eugenics - termed coined by Francis Galton in 1883 to describe the application of scientific knowledge about human inheritance to improve the human race by influencing who would reproduce.

Genome-wide Association Study (GWAS) - A GWAS involves looking for associations between a specific disease phenotype and a large number of genetic markers (usually 500,000 or more) selected to provide adequate coverage across the whole genome. GWAS is designed to detect common genetic variants having a moderate effect on risk for diseases that have a multigenic, rather than a single-gene, basis.

Missing Heritability - To date, GWAS have only been able to account for a small portion of the total heritability of the phenotypes being studied, including height, diabetes, blood pressure, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. The unaccounted for genetic variants, the missing heritability, is subject to much speculation as to whether it is due to rare genetic effects that are poorly detected using the GWAS strategy or common variants of modest effect, which in principle could be detected with very large sample sizes.

Radical Behaviorism - a movement within psychology during the earlier 20th century that held that individual differences in behavior reflected a history of external contingencies. While the radical behaviorists, such as John B. Watson, did not totally rule out the contribution of genetic factors to behavior, they were strong proponents of the nurture side of the debate.

Systems Approach - Rather than focus on the effect of individual genetic variants, a systems approach emphasizes investigating the effects of genetic variants within the broad context of the biological pathways in which they are involved.

Twin Studies - involve the comparison of the similarity of monozygotic (MZ, genetically identical) twins to that of dizygotic (DZ, genetically non-identical). If MZ twins are more similar than DZ twins, genetic influences may be inferred.

Authors

Matt McGue is a Regents Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Minnesota and a Guest Professor in the Institute of Public Health at the University of Southern Denmark. He is a behavioral geneticist, with primary interests in genetic contributions to personality, intelligence, substance abuse disorders and aging. He has published over 300 scientific articles and is past president of both the Behavior Genetics Association and the International Society for Twin Studies.

Irving Gottesman is a psychiatric geneticist who has devoted most of his career to the study of schizophrenia. He currently is Senior Fellow in Psychology and retired from the Bernstein Professorship in Adult Psychiatry at the University of Minnesota. He has published over 300 papers and books, is a past president of the Behavior Genetics Association and has won numerous awards including the Dobzhansky Award from the Behavior Genetics Association, the Award for Distinguished Scientific Contribution from the American Psychological Association, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics.